With his permission, I am publishing his most recent newsletter, which focuses on Africa in general and Nigeria in particular. It should be noted that the newsletter was published on Jan. 18, 2006, just before the recent round of assaults, kidnappings and terrorist bombings began in the Niger Delta. The World Security Network briefing here was not only timely and prescient, but provides some important strategic guidelines for the successful prosecution of fundamentalist Islamic terrorism.

With no further ado, here is World Security Network's Jan. 18 newsletter:

World Security Network Foundation, New York, January 18, 2006

Dear Joe Shea,

The world’s attention is drawn to the current major crises in the so-called “Broader Middle East,” including the “arc of instability” from Marrakech to Bangladesh – extending to the east to North Korea as well as extending to the Caspian and Caucasus region. That people throughout the world and relevant governments focus on these crises is quite understandable but dangerous. Almost daily, we learn a lot about terrorist and extremist activities in these regions.

It might well be that the world will once more receive a wake-up call – this time from Africa. We cannot wait until the problems in Afghanistan, Iraq and Israel/Palestine have been solved. Then it might be too late to avoid a new theater of war on terrorism. By then the “cancer named terrorism” might have spread and strengthened its metastasis in the body of Africa.

Why is Africa so low on the international agenda? The flood of bad news coming from Africa – Somalia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Congo, Eritrea etc – has created a mixture of frustration, resignation, fatalism and hopelessness in the Western world. Poor results after decades of foreign aid, news of about 30 million HIV/AIDS infected people and the millions of orphans caused by this epidemic, information about corruption and poor governance in most African states as well as ongoing intrastate and interstate conflicts caused by ethnic and religious conflicts and the fight for strategic resources dominate the headlines. Good news is hard to find: Botswana and the Republic of South Africa seem to be the only lighthouses in Central and Southern Africa.

There are initiatives from the G8, the UN, the EU, NATO and the US – to name a few – to support Africa via the African Union and bilaterally, but so far these efforts are obviously insufficient to achieve remarkable progress. Support of Africa does not mean that more money should just be poured into corrupt systems. Foreign aid should go into concrete projects tightly controlled by the donors. Foreign aid should help and enable African people to help their countries.

Time works to the advantage of international terrorism and against world security. The number of failed states – serving terrorists as safe havens – is increasing. Poor governance and poor leadership, corruption, social and economic problems create the breeding ground for terrorist organizations and their recruitment of young people. This is combined with the spreading Islamization of Africa.

Islam is a priori not equal to terrorism.

But there is always a minority within the Islamic community in favor of extremist and terrorist activities. The terrorists in Africa cooperate with those involved in organized crime. Both benefit from the richness of raw materials that they trade illegally, gaining a lot of money. Africa will gain more importance as a world supplier of crude oil, gas and strategic raw materials.

Terrorism in Africa – including piracy – is a threat to the vital interests of Africa and the rest of the world. Western governments have to devote human, intellectual, economic and financial resources to immediately start confidence building measures and to install a common early warning system enabling crisis prevention.

With this newsletter, we offer an in-depth analysis of a young German academic whose studies focus on Africa. WSN totally agrees with two of his main recommendations:

“It therefore must be a key priority to Europeans and Americans alike to maintain more control over Africa’s economy and to promote border control by the African state authorities.”

“Development assistance is a necessary prerequisite for peace and freedom in Africa. It is furthermore indispensable if the West wants to win the war on hearts and minds.”

Dieter Farwick

Global Editor-in-Chief

Worldsecuritynetwork

Why Africa matters

Terrorism in Africa - the forgotten continent once more?

written by: Dustin Dehéz

“As terrorists operate flexibly and internationally, so must we.”

The G8 on the 8th July 2005

Rising Stakes in Africa

During the 1990s, after the end of the Cold War, Africa seemed to have become what some observers have called “the forgotten continent“. After 9/11, international attention focused on the Middle East as a main hotspot of new conflicts. For a moment, though, there seemed to be a window of opportunity, a chance that Africa might surface on the international agenda again. General Tommy Franks argued in a dialogue with Senator Bob Graham:

“We can finish the job in Afghanistan if we are allowed to do so. And there are a set of terrorist targets after Afghanistan. My first priority would be Somalia. There is no effective government to control the large number of terrorist cells.“1

One of the reasons why Africa deserves international attention is actually the war on terror. For international terrorist networks Africa is a main target; it serves as a safe haven and provides an effective financial basis with its large networks of informal economies. Africa has furthermore slowly emerged as one of the key strategic fields of international resources.

The oil in the Gulf of Guinea is of major interest to the United States and Europe alike. The U.S. currently imports some 16% of its total oil imports from the African continent, Nigeria being one of its five most important oil suppliers. During the next four or five years these figures will rise substantially to some 25%. It's not only oil that is driving the interests of nations and corporations, its also other raw materials like coltan for relatively new industrial products, like mobile phones.

The rising importance of African resources for the United States and Europe is particularly worrying as Africa had become what some have called the “underbelly for transnational terrorism”.2 Largely unnoticed major parts of Africa have been the scene for Islamisation since the late 1970s. It is this mixture of strategic resources, Islamisation, and state weakness that makes Africa so an inviting target for terrorism and terrorist networks.

Terrorism in Africa

The fact that terrorism has emerged as one of the most dangerous threats to the West was by no means a surprise. Back in 1995 the NATO Secretary General Willy Claes warned:

“Islamic militancy has emerged as perhaps the single gravest threat to the NATO alliance and to Western Security

The threat by fundamental Islam in Africa has to be taken seriously.

Source: http://worldsecuritynetwork.com

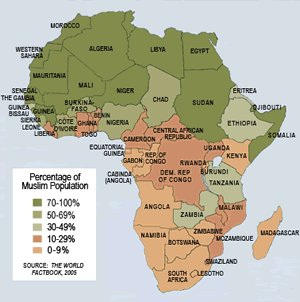

In sub-Saharan Africa Islam has advanced significantly in the last couple of years. Some analysts fear that Niger may break up; into a Muslim dominated North and a Christian dominated South. Ethiopia, Nigeria and Senegal also have strong Muslim minorities.4 Some analysts go as far as claiming that there are already centres of Islam in Africa, considering the tropical zone along the Gulf of Guinea, the Sudanese Nile region and the East African coastal strip as such centres of Islam.5

There are strong Muslim minorities in Mocambique, Uganda, the Central African Republic (CAR), Liberia, Burkina, Tanzania, Sierra Leone, Cameroon and Côte d'Ivoire. In some other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa Islam is already a majority religion: Djibouti, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Somalia.6 In Nigeria for instance some twelve provinces introduced the Shari’a as basic law and Osama bin Laden called it one of the countries he wanted to “liberate”.7

Somalia serves a safe haven for terrorist groups like Al-Itihaad al-Islamyia, which is linked to Al-Qaeda. This particular terrorist cell is held responsible for the attacks on U.S. soldiers during the U.N. mission Restore Hope, which left 18 U.S. soldiers dead and about 75 wounded.8

Islam is one index of identity, alongside ethnicity and regional loyalties and so far African Islam has been relatively moderate. But as David McCormack recently pointed out, African Islam is slowly turning into Islamism in Africa.9

In West Africa one of the major reasons for the instability of the coastal strip and its countries like Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Côte d'Ivoire, and Liberia is the divison into a Christian-dominated South and a Muslim-dominated North. More aggressive interpretations of Islam are promoted by Saudi Arabia and Iran, through building of mosques, financial support for the hajj and the provision of education. The presence of the Muslim World League and the World Assembly of Muslim Youths in East Africa has had a radicalising influence on the local population.10 The threat by fundamentalist Islam in Africa has to be taken seriously.

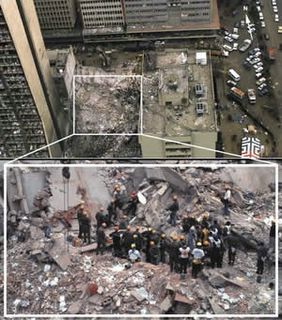

Three years before 9/11, Africa was targeted by Al-Qaeda. The attacks on the U.S. embassies in Dar-es-Salaam and Nairobi caused 224 casualties, including 12 Americans. Since 1996 the number of international terrorist incidents in Africa increased dramatically. While in 1996 eleven incidents had been reported, the number exploded to fifty-five incidents in 2000.11

Although Africa is comparatively less effected by international terrorism (although it experienced some of the bloodiest attacks)12 that does not indicate that it deserves less attention. Quite on the contrary, it should be one of the major focuses in the struggle against terrorism.

The core problems the international community has to face on the African continent are:

- ungoverned parts of Africa, especially in failed states, which often serve as safe haven for terrorists and other states that serve as transit hubs to the Middle East, like Kenya;

- conditions of conflict that may lead to more alienation from traditional identities and thus providing breeding ground for more radical forms of Islam;

- that nearly 40% of Africa's total population are already Muslim, while a more fundamentalist version of Islam is promoted with financial backing from Saudi Arabia and Iran;

- that widespread guerilla warfare might turn into urban terrorism,13;

- that informal economic structures might serve as an ideal environment to money laundering,14;

- and finally that Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs), donors, and other Western institutions might provide an easy and inviting target for international terrorism.15

Given this background one might wonder, why Africa did not experience more terrorist attacks in the past.16 The main reason is that failing states provide a suitable environment for sub-national terrorism. But sub-national terrorism does not count as international terrorism, that has, per defintionem, to affect more than one country.17

While weak and failed states with their lack of territorial control make it easier for opposition movements or potential terrorist organisations to seize power. Groups that do not have the ability to control territory – as is the case in most countries in the Middle East – tend to terrorist strategies. But as long as these opposition groups maintain territorial areas of control they do not tend to terrorist attacks; they prefer what some analysts label guerilla warfare.18 Guerilla warfare is by no means less brutal than other forms of terrorism; the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda and the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone proved that their guerilla warfare is indeed yet another form of terrorism.

Collapsed US Embassy Building in Nairobi, Kenya, August 7, 1998.

The African Union's regional instrument to counter terrorism is the Algiers Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism established in 1999.19 It defines terrorism as a form of international crime: a result of the fact that Africa serves as a suitable and ideal environment to finance terror. African states realised back to two years before 9/11 that terrrorism exploits the differences in governance, porous borders, and illegal and informal trade networks.20

After the attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 1373.21 This resolution was binding and called for the suppression of the recruitment, financing and supply of terrorist networks (although many African governments committed themselves to the war on terror, they lack the means to effectively do so). In the same resolution the United Nations Security Council was aware that one of the major problems is the connection between terrorism and international organised crime. This especially concerned Africa, where drugs and arms trafficking and informal economic structures are prelevant.22

Strategic Resources and International Terrorism

Africa with its huge networks of informal economy is furthermore a suitable environment for terrorist groups to finance themselvs. There are rumours that Al-Qaeda profited from the informal economic structures in Africa. Although there is not yet enough evidence, many analysts think its plausible that Al-Qaeda was involved in the diamonds trade in Sierra Leone and in gems trafficking in Tanzania, thus prolonging tensions and conflicts.23 Some observers even argue that Al-Qaeda owned up to nearly 15 vessels for any kind of transport, using Somalia as an operational basis. Additionally there are also reports that Al-Qaeda was involved in Gold smuggling from Pakistan to Sudan.24

What makes Africa so attractive and vulnerable to terrorists and international crime is its resources. Especially in West Africa and in the Gulf of Guinea there are vast amounts of oil. Gold, iron ore, bauxite, diamonds, and uranium attract not only big Western companies but also illegal and informal entrepreneurs. In Central Africa gold, iron, oil, diamonds do the same; coltan is also available, which is especially important for those industries producing mobile phones and other electronic equipment.25

As the United States want to increase the African part of their oil supplies, more attention will be drawn to Nigeria, Chad, Congo (Brazzaville), Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Sao Tomé e Principe.26 Some 25% of overall U.S. oil imports will come from Africa within the next four or five years.27 But the security sector in Africa is weak and on-shore as well as off-shore oil production is a very inviting target, especially in Nigeria.

In the past mineral resources played a key role in financing civil war and different militias. Illegal diamond trade was a major source to finance the war between the Angolan government and the UNITA.28 The instability in the Democratic Reublic of Congo is largely due to the attractiveness of a vast amount of mineral resources in the region. Their illegal exploitation is a central way of financing for different milita groups in the whole country.

One central precondition of illegal exploitation are porous borders. The smuggling of diamonds and other raw materials across the borders in central Africa is a key obstacle to freedom and peace in the region. As long as illegal trade is that simple providing stability in the region will be very difficult even for democratic states; and missions to provide stability in the region are designated to fail, as attacks on MONUC soldiers in the province of Ituri in early 2005 showed. It therefore must be of a key priority to Europeans and Americans alike to maintain more control over Africa's economy and to promote more border control by the African state authorities.

A Change in Policies?

After 9/11 the United States reviewed its foreign and development policy. One basic conclusion was that despite all international aid and financial injections most development countries in Africa simply did not experience development. The National Security Strategy set up in 2002 was the first attempt to counter that challenge. No development in development countries however did not suggest that development aid was futile, but rather that development aid had to be conducted in a different way.

The new National Security Strategy marked the first time the United States began to take the threat of failed and weak states seriously. The U.S. tried to tackle the issue and committed itself to more development aid but at the same time made it part of their National Security Agenda. Development policy since then has a goal: Improving security for the United States and their allies. It was no longer a senseless expenditure to prove the selflessness of Western nations but was turned into an important means of foreign and security affairs, thereby giving it a much higher priority in overall political affairs.

However, until now this change has only been rhetorical. State failure and state weakness in Africa is still a widespread problem. Somalia is an outstanding case in this regard. It experienced a military coup d’etat in the early postcolonial period, was an ally to both the Soviet Union and the United States, entered a bloody civil war, followed by international intervention and withdrawal and the secession of a major part of the country, of what is now called Somaliland.

But renewed efforts by the African Union and the regional body, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) go without significant support of the United States. State failure is an imminent threat in other African countries as well, as in Nigeria and Eritrea.29 There is a whole volatile region from Liberia to Nigeria in the Gulf of Guinea where state failure is a common threat, thus preparing a potential breeding ground for terrorism in the medium future. But despite the rising significance of these regions for their natural resources initiatives to promote peace, stability and democracy have been limited.

Although after 9/11 the United States released a new doctrine – the U.S. now considers Kenya, Nigeria, Sudan and Ethiopia as key countries of their interest in Africa – in the very same doctrine the United States stated that no U.S. troops will be dispatched to the African continent in peacekeeping missions.30 The same goes for the G8 countries: Although they have recognised that “Sustained and better co-ordinated support for the African Peace and Security Architecture and for post-conflict is required”31, they have not yet allocated the necessary financial support nor have they increased their diplomatic activity.

Recommendations – Avoiding a deja vu

When in 1989 the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan not all Mujahedin stayed in Afghanistan, many wanted to continue the fight for radical Islamisation elsewhere and subsequently went to Algeria or Somalia. It could happen all again, as soon as Iraq is more stable foreign fighters might again focus on other possible targets and as in the early 1990s they will surely try to penetrate Africa and make use of its state weakness. With a costly war in Iraq still looming what could the West, the United States and the G8 do to prepare itself and Africa for the upcoming battle?

- The Joint Task Force Horn of Africa is a very good start, but its mandate is absolutely insufficient. Ships must be boarded if they are suspicious of carrying weapons or terrorists, not if their crew permits it. It is striking that despite the presence of a maritime force piracy at the Horn of Africa is still a widespread problem and is even increasing. The current mandate should be revised and allow for extended policing rights. In doing so the UN arms embargo against Somalia could be enforced, efforts of state-building in Somalia would be promoted and piracy would be better responded to.

- Programmes for the training of African peacekeepers must be enhanced and united under one common umbrella. The current practice that France, Britain and the United States are each running their own programme for training is provoking a latent rivalry and is used as ammunition by critics of the West and the media in Western Europe to illustrate what they see as a struggle of these three countries for more influence in the region. The G8 countries committed themselves to the training of 75.000 peace keepers, but streamlined and united within the framework of a NATO mission these programmes could be more effective.32

- Development assistance is a necessary prerequisite for peace and freedom in Africa. It is furthermore indispensable if the West wants to win the war on hearts and minds, but instead of funding African governments the focus should shift to infrastructural projects. More and better roads would not only allow foster economic development, but would furthermore enable better state integration and would as a result strengthen weak states.

- The major obstacle to lasting peace in Africa is the relatively easy access to small arms and light weapons. An estimated 100 million small arms are currently on the markets throughout Africa. Countering arms smuggling goes hand in hand with more effective border control. The capabilities of African states to monitor their own borders must be enhanced significantly and a new small arms regime must be imposed to counter the spread of small arms. Only if the prices for weapons and ammunition are increasing sharply the price for waging civil war might be too high for warlords throughout the continent.

- The G8 rightly pointed out that progress in Africa “depends above all on its own leaders and its own people.”33 Good governance is therefore a key necessity for development and for lasting peace and should be promoted by the West.

- Islamisation of East Africa and Nigeria is a particularly worrying development. The United States and the European Union must foster initiatives to counter increasing Saudi and Iranian influence in East Africa. The building of mosques, financial support for the hajj and providing education has created a fertile ground for radical Islam in major parts of East Africa, particularly in Kenya, especially Zanzibar, Somalia and Tanzania. What is needed is a combined approach including development assistance and support for more liberal Muslim clerics.

- The promotion of safety for critical infrastructure in Africa is perhaps the most urgent challenge to the West. Not only borders are largely uncontrolled, even crucial infrastructures like harbours and airports are in need of tightened control. The international community should strengthen and support African capabilities to monitor movements on these critical infrastructural networks.

1 Tommy Franks to Senator Bob Graham. This quote appeared on the H-Mideast Politics discussion network (http://www.h-net.msu.edu)

2 Mentan, Tatah: Dilemmas of Weak States. Africa and Transnational Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century. Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate, 2004, p. 2.

3 Warraq, Ibn: The Enemy: "Terrorism?" In: African Geopolitics, 5 (Winter 2001/2002), pp. 99-113.

4 Belmessous, Halène: The Progress of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: African Geopolitics, 5 (Winter 2001/2002), pp. 77-83.

5 Mair, Stefan: Terrorism and Africa. On the Danger of Further Attacks in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: African Security Review, 12 (1/2003), pp. 107-110.

6 Guérivière, Jean de la: The Different Faces of Black Islam. In: African Geopolitics, 5 (Winter 2001/2002), pp. 69-76.

7 Herbst, Jeffrey/Mills, Greg: Africa and the War on Terror. In: South African Journal of International Affairs, 10 (2/2003), pp- 29-39.

8 Cornwell, Richard: Short Commentary on Somalia: Plus ça Change…? Institute for Security Studies Situation Report, 19/1/2005; Otenyo Eric E.: New Terrorism. Toward an explanation of cases in Kenya. In: African Security Review, 13 (3/2004), pp. 75-84; Nielinger, Olaf: Afrika und der 11. September 2001. In: Afrika Spektrum, 36 (1/2002), pp. 259-272, and Nord, Antonie: Somalia und der internationale Terrorismus: Wie stark sind islamistische Fundamentalistin am Horn von Afrika? In: Afrika im Blickpunkt, (1/2002), pp. 1-9.

9 McCormack, David: An African Vortex: Islamism in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Center for Security Policy. Occasional Papers Series, No. 4, January 2005, p. 3.

10 McCormack, David: An African Vortex: Islamism in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Center for Security Policy. Occasional Papers Series, No. 4, January 2005, p. 6.

11 Hough, Mike: New York terror: The implications for Africa. In: Africa Insight, 32 (1/2002), pp. 65-70.

12 Cilliers, Jakkie: Terrorism and Africa. In: African Security Review, 12 (4/2003), pp. 91-103.

13 Clapham, Christopher: Terrorism in Africa: Problems of Definition, History and Development. In: South African Journal of International Affairs, 10 (2/2003), pp. 13-28.

14 Wannenburg, Gail: Links between Organised Crime and Al-Qaeda. In: South African Journal of International Affairs, 10 (2/2003), pp. 77-90.

15 The World Food Programme (WFP) and Medeciens Sans Frontieres had been under attack in Africa in 2001. Cilliers, Jakkie: Terrorism and Africa, p. 99.

16 The report “U.S. patterns of Global Terrorism 2003” for instance counted twelve terrorist organisations active in Africa, while eight terrorist organisations have been counted active in Northern Ireland alone. US Patterns of Global Terrorism 2003, pp. 113-160. In general on the matter: Krueger, Alan B./Laitin, David D.: “Misunderestimating” Terrorism. The State Department’s Big Mistage. In: Foreign Affairs, 83 (5/2004), pp. 8-13.

17 Cilliers, Jakkie: Terrorism and Africa.

18 Clapham, Christopher: Terrorism in Africa.

19 Sturman, Kathryn: The AU Plan on Terrorism. Joining the Global War or Leading an African Battle? In: African Security Review, 11 (4/2002), pp. 103-108.

20 The United States created the Pan-Sahel Initiative (PSI) to counter the effects of porous borders and to help the governments of Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Chad to control their borders. US Patterns of Global Terrorism 2003.

21 Cilliers, Jakkie: Terrorism and Africa.

22 Malan, Mark: The Post-9/11 Security Agenda and Peacekeeping in Africa. In: African Security Review, 11 (3/2003), pp. 53-66.

23 Mair, Stefan: Terrorism and Africa

24 Wannenburg, Gail: Links between Organised Crime and Al-Qaeda. Some reports suggest that the Task Force Horn Of Africa that is currently patrolling the waterways at the Horn of Africa is tracking more than twenty ships believed to be controlled by Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda. http://allafrica.com/stories/printable/200511070308.html.

25 Mair, Stefan: Die regionale Integration und Kooperation in Afrika südlich der Sahara. In: APuZ, B 13-14 (2002), pp. 15-23.

26 Basedau, Matthias/Mehler, Andreas: Strategische Ressourcen in Subsahara Afrika. Konfliktpotenziale oder Friedensgrundlagen? In: Internationale Politik, 58 (3/2003), pp. 39-46.

27 Kansteiner III, Walter: Political Reforms are Essential in the Fight against Terrorism. In: African Geopolitics, 5 (Winter 2001/2002), pp. 31-35.

28 Dietrich, Christian: Blood Diamonds. Effective African-based Monopolies? In: African Security Review, 10 (3/2001), pp. 99-114.

29 In the case for Eritrea, see: West, Deborah L.: Terrorism in the Horn of Africa and Yemen. Program on Intrastate Conflict. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard University, 2005.

30 Cilliers, Jakkie: Peacekeeping, Africa and the Emerging Global Security Architecture. In: African Security Review, 12 (1/2003), pp. 111-114.

31 The G8 Progress Report by the Africa Personal Representatives on implementation of the Africa Action Plan, p. 7.

32 The G8 Gleneagles Communique, § 8 and 9.

33 The G8 Gleneagles Communique, § 5.

No comments:

Post a Comment